The National Labor Relations Board did not err in holding a sandwich store chain violated the National Labor Relations Act by disciplining and terminating employees for placing posters on community bulletin boards in the public areas of several of its locations suggesting the chain required sick employees to come to work and make sandwiches, the federal appeals court in St. Louis has ruled. MikLin Enters., Inc. v. NLRB, No. 14-3099 (8th Cir. Mar. 25, 2016).

MikLin Enterprises owns and operates several Jimmy John’s restaurants in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It had a sick leave policy that required employees to find replacement workers when they called out sick. Several employees attempted to persuade the company to change the policy by placing posters on community bulletin boards. According to the court, the posters:

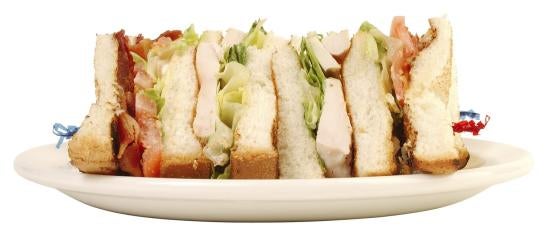

featured two identical, side-by-side photographs of a sandwich…. Above the left sandwich was a label stating: “Your Sandwich Made By A Healthy Jimmy John’s Worker.” Above the right sandwich was a label stating: “Your Sandwich Made By A Sick Jimmy John’s Worker.” Below the photographs, the poster stated: “Can’t tell the Difference?” “That’s Too Bad Because Jimmy John’s Workers Don’t Get Paid Sick Days.” “Shoot, We Can’t Even Call In Sick.” “We Hope Your Immune System Is Ready Because You’re About To Take The Sandwich Test.”

MikLin removed the posters, but . . . the employees then posted the flyer in public areas surrounding several Jimmy John’s restaurants. Those flyers also included the telephone number of MikLin’s co-owner and vice-president. The employer did not change its sick leave policy.

MikLin fired six employees for “being the leaders and developers” of the flyer campaign and disciplined three others for being “foot soldiers” in the campaign.

Unfair labor practice charges were filed against MikLin alleging violations of the NLRA. By a 2-1 vote, the NLRB held the flyers were “sufficiently related to an ongoing labor dispute to be protected and that there was nothing in the posters that was so disloyal, reckless, or maliciously untrue so as to cause the employees to lose the Act’s protection.” It said that in order to lose the NLRA’s protection, a false statement has to be made with “actual malice,” which it defined as “knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth.” The Board held that actual malice was not shown in this case.

MikLin appealed, and in a 2-1 decision, the Eighth Circuit affirmed. Finding substantial evidence to support the Board’s decision that the flyer’s untrue claim that workers could not call-out sick was not so maliciously false as to place it outside the Act’s protection, it enforced the Board’s order.

Dissenting, Judge James Loken said the Board’s definition of malice was so narrow that it effectively removed employee disloyalty from the analysis. He would have found the employees’ knowledge of the statement’s falsity concerning their ability to call in when sick was sufficient to show a malicious intent to harm the employer, which was not protected. The discharge of employees, therefore, would not violate the Act, in Judge Loken’s opinion.

The decisions in this case raise questions about the signal they might send about employee latitude when publicly disparaging their employers and how employer and employee rights will be balanced.

i

i