In a 50-year game of ping-pong, the Biden administration marked the end of 2022 by taking its turn revising the definition of “waters of the United States,” or “WOTUS” for short. This term determines where Clean Water Act (CWA) permits are required for wetland dredging and filling and pollutant discharges, as well as other CWA jurisdictional limits. A pre-publication version of the “Revised Definition” WOTUS rule as well as additional guidance materials were released on December 30, 2022; though the regulation does not take effect until 60 days after its official publication (still pending).

The Clean Water Act regulates pollutant discharges to “navigable waters,” defined vaguely as “waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.” Congress failed to further define WOTUS when it adopted the CWA in 1972. Court decisions confirmed that the critical term includes more than just large, actually-navigable rivers and lakes, known as “traditional navigable waters.” However decades of litigation have failed to identify the limits of WOTUS in a manner acceptable to the regulated community, environmental groups, and the agencies charged with enforcing the CWA (the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Defense’s Army Corps of Engineers) (together, the Agencies).

The WOTUS interpretations debated most often today are the competing U.S. Supreme Court holdings in the split 2006 Rapanos v. U.S. decision. In the plurality opinion (garnering only four of nine votes), Justice Scalia limited WOTUS to “relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water [such as streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes]” and “adjacent wetlands” with a continuous surface connection to such waters. But Justice Kennedy authored a concurring opinion in Rapanos, arguing that WOTUS should also include wetlands with a “significant nexus” to traditional navigable waters (TNW) because they “significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity” of TNW. Supporters of the “significant nexus” trigger point to the CWA’s expressly-stated objective to “restore and maintain the … integrity of the Nation’s waters.” Followers of a narrower WOTUS definition counter that this CWA water restoration goal is not unlimited and must be balanced against the additional CWA objective “to recognize, preserve, and protect the primary responsibilities and rights of States to prevent, reduce, and eliminate pollution [and] to plan the development and use … of land and water resources.”

Through subsequent guidance, permitting, and jurisdictional determinations (JDs), the Agencies applied the “significant nexus” test to not only wetlands, but also tributaries and other water features believed to affect TNW. During the Obama administration, the 2015 Clean Water Rule was issued, formally revising the WOTUS definition to include a significant nexus trigger, while also codifying several exceptions for certain drainage, construction, and other features commonly allowed by the Agencies outside of CWA jurisdiction. The Trump administration returned the focus to Justice Scalia’s test by repealing the Clean Water Rule and volleying back with its 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR), limiting WOTUS to: traditional navigable waters and territorial seas; tributaries, lakes, ponds and impoundments that are perennial or at least intermittent in a typical year and that contribute surface water flow to TNW or territorial seas; and adjacent wetlands touching or closely connected to any such jurisdictional waters. The 2020 NWPR excluded most water features lacking a TNW surface connection, as well as “ephemeral” waters existing only in response to precipitation, while retaining express exceptions for the common drainage, construction, and similar features. Both the Obama and Trump rules triggered endless court battles and rulemaking initiatives – leading to the remand of the NWPR back to the Agencies, halting its implementation.

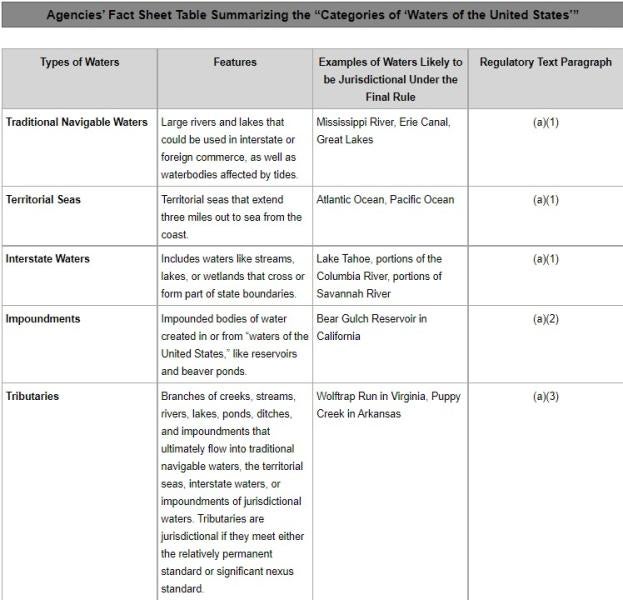

The Biden administration’s new rule applies the “relatively permanent” and “significant nexus” standards to identify the following categories of WOTUS:

The Agencies offer further comments on the WOTUS categories in their Final Rule Fact Sheet:

The Biden administration describes its new WOTUS definition as putting back into place the regulatory scheme in effect before the Obama and Trump administrations’ rulemaking efforts. But, by expressly including “significant nexus” triggers, the new rule more closely resembles the 2015 Clean Water Rule. The new rule goes further by adding new criteria [4] for determining when a water feature trips this trigger because it has a “material influence on the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of [TNW, territorial seas, or interstate waters],” either “alone or in combination with similarly situated waters in the region.” The Biden administration claims that the rule’s new terms and updated exceptions for ditches, construction site depressions, wastewater treatment ponds/lagoons, prior converted croplands, artificial ponds/irrigation areas, and similar features are supported by its extensive public outreach to agricultural, tribal, state, and other stakeholders. Countering longstanding criticisms that “significant nexus” considerations unduly burden farming, infrastructure, and other projects with complex and expensive study requirements, the Agencies also point to past guidance and additional materials now available to facilitate predictable WOTUS determinations.

Sackett v. EPA – While the Agencies’ new rule includes changes far exceeding their earlier “Rule 1” plans to only repeal recent WOTUS rulemaking, they are keeping in place a “Phase 2” placeholder to promulgate yet another “durable” WOTUS rule, to be “informed by the experience of implementing the pre-2015 rule, the 2015 Clean Water Rule, the 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule, and Rule 1.” The Biden administration may be positioning its Agencies to make future “Rule 2” WOTUS definition changes if the U.S. Supreme Court invalidates or cuts back the “significant nexus” trigger in a pending appeal brought by the Sackett family against EPA. In that case, EPA issued an order and a JD that applied the significant nexus test to prohibit further filling and home construction activities on the Sackett’s “soggy” property located 300 feet from Priest Lake, a TNW in Idaho. The wetlands on their 0.63 acre lot drain into the lake beneath the ground surface but, thanks to intervening roads and residences, have no surface connection to Priest Lake or any other TNW. The lot’s wetlands are part of a larger wetland resource that has been found to impact Priest Lake. The Ninth Circuit’s 2021 decision in Sackett affirmed summary judgment in favor of EPA based on the “significant nexus” test, rejecting the Sackett’s argument that Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion should control. The present appeal to the Supreme Court has been briefed and argued; a decision is expected later this year.

The Biden administration has also lobbed its new WOTUS definition into the Court’s deliberations on the Sackett case. The Office of the Solicitor General followed up on oral argument questions about the status of the rule by sending the Court a December 30, 2022 letter providing a link to the now “final rule.” In Sackett oral arguments, the Court also focused on a CWA provision that expressly refers to the Agency permit program applying in “wetlands adjacent” to TNW, indicating Congress’s intention to regulate at least some wetlands near TNW. In response to the Court’s related questioning on the uncertain extent of such wetland regulation, the Solicitor General points to the Agencies’ preamble comments describing which “adjacent wetlands” are regulated as WOTUS under their new rule. The Sackett’s attorney countered by pointing the Court to one statement in the CWA legislative history “interpret[ing] the word ‘adjacent’ to mean immediately contiguous to the waterway.”

EPA’s December 30, 2022 rule announcement seems to speak to both the Court and the public: “This rule establishes a durable definition of [WOTUS] grounded in the authority provided by Congress in the Clean Water Act, the best available science, and extensive implementation experience … The rule returns to a … framework founded on the pre-2015 definition with updates to reflect existing Supreme Court decisions, the latest science, and the agencies’ technical expertise.”

For now, the WOTUS ball is back in the hands of the Supreme Court. But, by forcing out its “durable” Phase 1 rule and reserving a place for potential Phase 2 rulemaking, the Biden administration is sending the Court and interested stakeholders a message that its Agencies are prepared to keep hitting back any narrow CWA interpretations sent their way in this game of WOTUS ping-pong, now entering into its sixth decade.

ENDNOTES

[1] Attorney Melvin’s additional articles and presentations on water and wastewater topics appear in the Environmental Law+ blog and other Robinson+Cole publications.

[2] Under federal regulations, “wetlands” are delineated under the following site-specific hydrologic and vegetation criteria: “those areas that are inundated or saturated by surface or ground water at a frequency and duration sufficient to support, and that under normal circumstances do support, a prevalence of vegetation typically adapted for life in saturated soil conditions.” 33 CFR §328.3(c)(1); 40 CFR §120.2(c)(1); see also Army Corps’ Wetlands Delineation Manual (1987 with regional supplements).

[3] “Adjacent” is defined in the rule as “bordering, contiguous, or neighboring” without regard to “man-made dikes or barriers, natural river berms, beach dunes, and the like.” are “adjacent wetlands.” 33 CFR §328.3(c)(2); 40 CFR §120.2(c)(2).

[4] “To determine whether waters, either alone or in combination with similarly situated waters in the region, have a material influence on the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of waters identified in paragraph (a)(1) of this section, the functions identified in paragraph (c)(6)(i) of this section will be assessed and the factors identified in paragraph (c)(6)(ii) of this section will be considered:

(i) Functions to be assessed: (A) Contribution of flow; (B) Trapping, transformation, filtering, and transport of materials (including nutrients, sediment, and other pollutants); (C) Retention and attenuation of floodwaters and runoff; (D) Modulation of temperature in waters identified in paragraph (a)(1) of this section; or (E) Provision of habitat and food resources for aquatic species located in waters identified in paragraph (a)(1) of this section;

(ii) Factors to be considered: (A) The distance from a water identified in paragraph (a)(1) of this section; (B) Hydrologic factors, such as the frequency, duration, magnitude, timing, and rate of hydrologic connections, including shallow subsurface flow; (C) The size, density, or number of waters that have been determined to be similarly situated; (D) Landscape position and geomorphology; and (E) Climatological variables such as temperature, rainfall, and snowpack.”

33 CFR §328.3(c)(6); 40 CFR §120.2(c)(6)

/>i

/>i